Monetary Union

Making the Single Currency work.

The train towards monetary union was rolling. Europe's leaders assembled in the small Dutch town to agree a treaty that would

shape and shake the continent. And the point about monetary union is that it was about much more than money.

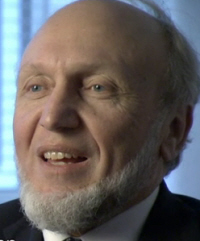

Lord Lamont "I was Britain's negotiator at Maastricht for the opt-out from the Euro. And I remember the very first time I met

Pierre Beregovoy, the French finance minister, who was later the Prime Minister of France. And I remember the shock I felt when

he said to me, 'My children will live in a politically united Europe and I think that is a great thing' and what I saw very

clearly was the force of the political will to create a monetary union and a political union."

The Euro Continental Union or Disparity

Elisabeth Guigou "Mitterrand believed that it was the first step towards political union. It was both the key to economic union as well as a first step towards political union."

Monetary union was a political project in economic clothing. And at its heart was a terrible contradiction. It was designed by

Mitterrand and Kohl to speed up the creation of a European Federation, a super-state. But pushing for monetary union before the

political union was in place carried enormous risks.

Lord Lamont

Lord Lawson

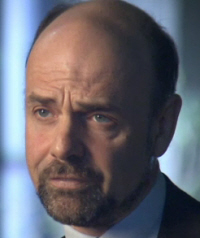

Lord Lawson "You cannot have a monetary union that works, without a fiscal union. You cannot have a fiscal union without, in

effect, a single finance minister, which means you have to have a full political union. You can only have the full political

union if the people are prepared to go along with it, and people are quite clearly not."

David Marsh "it was an impossible dream that you could build a single European currency without a single European state. Everybody

knew that it was a risk. Everybody knew that you were putting the cart before the horse."

Lord Lawson "it was arrogant because they thought that way they could override the democratic veto. And it was irresponsible because

they didn't say, 'Well, this is a high-risk project.' I think that was a gamble, if you like, should never have been taken."

"Maastricht is the beginning of a process of irreversibility, the creation of economic and monetary union."

But the monetary union would be without one of the biggest economies – Britain.

Lord Lamont "you know, the attitude was slightly condescending,'Oh! Norman, you say you don't agree with this, but when

the time comes, you will join.' That was what many people said. I remember one prominent figure, in the dead of night, about

two in the morning, over whiskey, saying to me, 'Well, everything you say is right, but it's going to happen.'"

There was a precursor to full monetary union, introduced before Maastricht, called the Exchange Rate Mechanism. Britain was

involved and it prevented the pound and other member currencies from old rising or falling more than a set amount relative to

Germany's Deutschmark.

David Marsh

David Marsh "Britain joined the ERM because it had tried many mechanisms to get inflation rates down, all sorts of monetary

devices. John Major saw the strong, successful Deutschmark, and he was fascinated by the Bundesbank. So he said, 'We'll have a little

bit of that.'"

The fate of Britain in the ERM shows the dangers of linking currencies when economies and governments aren't unified, foreshadowing

today's Euro crisis. Under the scheme, the interest rates for the UK where, in effect, set by Germany, but the right interest rate

for Germany turned out to be ruinous for Britain and UK was forced into a humiliating exit from the ERM on Black Wednesday, 1992.

Lord Lamont "today has been an extremely difficult and turbulent day. The government has concluded that Britain's best interests

are served by suspending our membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism."

The ERM debacle should perhaps have served as a warning about the dangers of linking currencies of very different economies.

But, instead it was full steam ahead for a single currency, but with new rules that were supposed to minimise economic tensions,

including a new ceiling on government debts.

Hans-Werner Sinn

Prof Hans-Werner Sinn "initially one had said, anyone who has a debt above 60% of GDP cannot participate. That would have kept

the Euro small. The southern countries, over-indebted countries, would not have been able to participate and, had they not

participated, we would not have today's problems."

Italy in particular had huge debts and the government debt criterion would have kept Italy outside the euro.

Gerhard Schröder

Gerhard Schröder "you cannot have a common currency in the EU without Italy. When it comes to the ratio of debt to GDP, Italy

has always broken the criteria. But Italy, as a founding member state of the EU, was too important to be excluded."

Prof Hans Werner Sinn "the French insisted at the time that the southern periphery of Europe participate and so they argued

that this 60% criterion, which was a firm entry criterion of the Maastricht Treaty, was waived."

The requirement that date should be 60% or less of GDP was dropped. Instead a country simply had to show it was reducing debt

towards that ratio, which Italy could do.

Of the major European economies, only Britain stayed out of the Euro when it was launched in 1998.

Ed Balls

Ed Balls "The risks associated with it became clearer and, you know, the phrase for… The Tony Blair phrase from 1997, he 'would

only join if the case is clear and unambiguous'. Gell, we didn't have a clear and unambiguous case."

The currency was born at a seemingly auspicious time. For the rest of the world, it was a time of sustained growth, cheap debt

and the consumer boom, which would last for the best part of another decade. Even in such benign conditions, some countries only

just met all the euro membership tests. How did they squeak in?

In the late 90s, an Italian economics professor, Gustavo Piga, was researching the way that governments borrow.

Gustavo Piga

Gustavo Piga "I was working on public debt management at the time. O knew there was this new trend, I started saying, 'Well

let's go around Europe to learn more' "

One tricky hurdle to joining the euro club was not a government deficit, the gap between what it spends and tax revenues,

had to be 3% or less of GDP. Piga became suspicious that banks had been helping governments to understate their true deficits.

Gustavo Piga "I got a sense that, in that period, some governments were using derivative transactions so as to ensure that

the level of the threshold of 3%, required to enter into the euro, was respected."

These complex financial derivative deals, arranged by banks, helped governments hide what they were borrowing.

Gustavo Piga "One day, I was interviewing one of these public debt managers and this person gave me a contract. She thought

that I knew little of derivatives and she said, 'Oh, Professor, if you want, I can show you an example, and she gave me a

photocopy.'. I started looking at it and I saw that it was a peculiar contract. And then I started getting excited and I

said, 'What is this?' And I understood that these contracts were meant exactly to reduce public deficit today, to enlarge

it 10 to 15 years later, in a way that an accountant would have said 'This is not proper.'. "