Renaissance, Europe’s Rebirth - Leonardo da Vinci

Now brimming with wealth from trade and new ideas from around the world, Christian scholars who had fled from Constantinople found these buzzing towns to be citadels of knowledge, and from within their walls, Europe would be reborn.

The Renaissance. Europe’s rebirth. Well, it was a long and painful birth - it went on for about 200 years. We’re told that the Renaissance was all about the rediscovery of classical learning, and it’s absolutely true that in this period the great Latin and Greek writers begin to bubble back into Europe’s consciousness.

But, really, the Renaissance is about the new. New ways of building, new ways of painting and making, new money and new confidence. Not coming from empires or nation-states but from the great city-states of Europe and, in particular, the great city-states of northern Italy. Genoa. Pisa. Florence. Venice. And Milan.

Ludovico Sforza

1495. For 13 years, Leonardo da Vinci had been employed at the court of the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. Every week, he bombarded the Duke with new ideas and schemes for portable bridges, fighting machines… Deep-see diving suits? His talents where prodigious. A prolific inventor, he was also a musician, an engineer and an artist, and he had found the perfect place to fulfil his talents.

Milan in the late 15th century was the wealthiest city in Italy. With its ambitious Duke, it offered a fertile environment for new thinking, risk-taking. The duke’s family, the Sforzas, were part of a new political class who’d grown rich from Europe’s ever-expanding trade networks. Like present-day oligarchs, they dealt in money and power, but what they craved was respectability.

Ludovico wasn’t exactly aristocracy. His father had been a mercenary warlord who kept changing sides. Fight absolutely anybody. And he’d ended up effectively grabbing Milan. The Sforzas didn’t exactly need bling, but they needed some class. They needed some artistic bedazzlement to try to make the people out there forget where they’d come from.

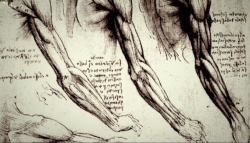

Leonardo da Vinci was paid to provide this. But he wasn’t a day-job kind of man. He filled notebooks with sketches and scribbled thoughts, taking into the underlying structures and curious parallels he found all around him in nature. In Leonardo’s time, there is no division between art and science. The artist studies the laws of perspective, works out how colours change, looks very closely at the underlying structure of things. The artist learns how to grind lenses to look more closely, learns how to cast metal to create a statue. Science is just knowledge, and learning the practical skills which allow other things, including art, to be made.

And now the Duke gave Leonardo da Vinci a chance to pull together his studies of geometry and perspective and human anatomy for one spectacular painting.

Santa Maria delle Grazie

Ludovico Sforza commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to paint Christ’s Last Supper with his 12 disciples on the wall of the monk’s dining room in the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It was a traditional scene, one that had been painted many times before. Above all, the duke wanted his Last Supper to be big and impressive. But Leonardo realised this was an opportunity to do something genuinely new.

Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed by the now and the future. He was a compulsive experimenter. Like modern scientists, he was fascinated by finding the hidden patterns underneath the reality. He wasn’t about looking back. He was about looking better, looking more intently, looking around him and looking ahead.

Leonardo decided to freeze one dramatic moment in time. The climax of the story, when Christ revealed to his disciples that one of them would betray him. And every posture, every gesture, every facial expression in the painting would be taken from real life.

Leonardo ransacked the streets of Milan looking for faces for the disciples. The really difficult one was Judas. And, apparently, he spent nearly a year looking for somebody with the right mix of cruelty and evil to play Judas.

Leonardo da Vinci drew on a series of his own anatomical sketches to capture the essence of human expression. Slowly, the painting and its characters began to emerge. Finally, after three years of painstaking work, the Last Supper was finished.

Art and science had come together in miraculous harmony. Leonardo had humanised the disciples by allowing them to show raw emotions. Shock. Grief. Anger. Building on Islamic scholarship of optics and perspective, he draws our eye to Christ at the centre of the table. Everything radiates from him.

For the people who first saw it, this would have been almost like a hallucination. Sitting and eating in this room, they would have been drawn towards Christ almost as if they were sitting and eating with Christ in person. In its day, this was the shock of the new.

Leonardo da Vinci remains a standard-bearer for the new confidence of Christian Europe, but its journey to Renaissance was far more than simply a European story. That muddy backwater had absorbed wealth and ideas from all around the world. Some of the mud was no paved with marble, and the backwater now thronged with merchants’ ships, adventurers.

Europe was ready to spread her sails.