Vibrant Islam - Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi

Inside that border, Christian Europe still seemed unsophisticated, a bit ploddy. Particularly compared to the vibrant, intellectual culture developing across huge areas of the world under Islam.

The year 827. A team of astronomers and mathematicians was at work in the Sinjar Desert, in north-western Iraq. They were led by Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi, an Uzbek scholar from the House of Wisdom, the great centre of Islamic learning in Baghdad, itself the heart of the new Muslim civilisation.

Al-Khwarizmi was struggling with one of the biggest scientific puzzles of the time - trying to accurately measure the circumference of the Earth. This trek across the desert was only the first stage in a project which had been commanded by the Caliph of Baghdad, Al-Ma’mun, who wanted him to use his great scientific understanding to produce an accurate map of the world which would show the huge extent of the Islamic Empire.

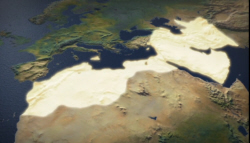

Islam already dominated an area bigger than the Roman Empire. By the ninth century, Muslim rulers had more than 30 million subjects, stretching from today’s Pakistan in the East to Spain in the West.

This is the age of vigorous, young, inquisitive Islam, bringing together ancient texts from all around the world, trying to understand them, pushing forward in science and maths. This is Islam’s golden age.

Measuring Planet Earth

Al-Khwarizmi’s idea was to measure the Sun’s angle to the Earth until it changed by one degree. He worked out that his men had walked 64.5 miles before the angle changed. Using just sticks and a simple brass instrument, he calculated the circumference of the earth to be 23,200 miles - a figure that, remarkably, is very close to the accurate, modern calculation.

Al-Khwarizmi went on to create a series of charts, listing more than 2,000 cities and geographical features right across the Islamic Empire. Al Khwarizmi was taking breakthroughs in trigonometry and arithmetic and putting them together and explaining them. His books were still being used hundreds of years later, and has real speciality was algorithms. In fact, the word comes from the Latin version of his name, Al-Khwarithmi.

And of course algorithms are essential in modern computer programming, so every time you pick up your mobile phone, remember, there is an old Uzbek Muslim hidden inside it.

At this time, the Islamic world had Christian Europe surrounded. The Spanish city of Cordoba was a glittering western outpost of the Muslim world, and the second-largest city on the planet, after Baghdad. It was a sparkling rebuke to the more meagre, muddy Christian kingdoms of Northern Europe. At its centre stands the Great Mosque. In its praying hall shimmer 850 pillars of marble, Onyx and Jasper, an imaginative mingling of Roman columns and the memory of palm trees in some distant oasis.

Fusion architecture.

Cordoba’s Royal library was said to hold 400,000 books, at a time when the largest Christian libraries contained a few hundred. And where East met West, ideas were shared. Places like Cordoba were wonderful at taking the news from one part of humanity and passing it on, so, ancient Greek learning, Jewish philosophy, Hindu mathematics, Muslim astronomy and engineering were passed to the Christian world. Eventually, the Christians would destroy the kingdoms of Al-Andalus, but not before one enemy had passed on the torch of learning to the next, so about what we call the Dark Ages was lit up by Muslim Spain./p>

At this point, you might have assumed the Islamic world would just keep advancing, that the future was scientific and Muslim.

The answer to why it wasn’t can be found in another story from the margins.