Hydrothermal Vents

Sub-Oceanic, Lost City

What is Life?

Sub-Oceanic Lost City

These are pictures from deep below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, somewhere between Bermuda and the Canaries. And it's a place known as the

Lost City. You can see why. Look at these huge towers of rock, some of them 50-60 metres high, reaching up from the floor of the Atlantic and into

the ocean. It's what's known as a hydrothermal vent system. So these things are formed by hot water and minerals and gases are rising up from deep

within the Earth.

But the reason it's thought that life on Earth may have begun in such structures is because these are very a unique kind of hydrothermal vent

called an alkaline vent. And, about 4 billion years ago, when life on Earth began, seawater would have been mildly acidic. So, here is that proton

gradient, that source of energy for life. You've got a reservoir of protons in the acidic seawater and a deficit of protons around the vents.

And the vents don't just provide an energy source. They are also rich in the raw materials life needs. Hydrogen gas, carbon dioxide and minerals

containing iron, nickel and sulphur.

But there is more than that. See, these vents are porous – there are little chambers inside them – and they can act to concentrate organic molecules.

Monarch Butterfly

Volcanic Island

You've got everything inside these vents. You've got concentrated building blocks of life trapped inside the rock. And you've got that proton

gradient, you've got that waterfall that provides the energy for life. So this could be where your distant ancestors come from. And places like

these could be the places where life on Earth began.

The first living things might have started out as part of the rock that created them. Simple organisms that exploited energy from the

naturally-occurring proton gradients in the vents. And we think this because living things still get their energy using proton gradients today.

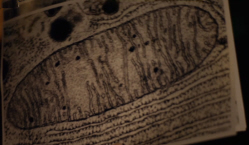

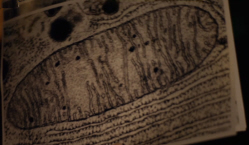

Deep within ourselves, the chemistry the first life exploited in the vents is wrapped up in structures called mitochondria – microscopic

batteries that power the processes of life.

Mitochonfria, Brown Bat

This is a picture of the mitochondria from the little brown bat. This is a picture of the mitochondria from a plant. It's actually a member of

the mustard family. This is a picture of the mitochondria in bread mould. And this of mitochondria inside a malaria parasite.

So, the fascinating thing is that all these animals and plants, and in fact virtually every living thing on the planet, uses proton gradients to

produce energy to live. Why?

Colourful Coral

Well, the answer is probably because all these radically different forms of life share a common ancestor. And that common ancestor was something

that lived in those ancient undersea vents, 4 billion years ago, where naturally-occurring proton gradients provided the energy for the first life.

So, if you're looking for a universal spark of life, then this is it. The spark of life is proton gradients.

In those 4 billion years, that spark has grown into a flame. And a few simple organisms clustered around a hydrothermal vent have evolved

to produce all the magnificent diversity that covers the Earth today.