Doomwatch

The awakening of Ecological Awareness

Our Planet

The sunny optimism of the affluent '60s had long since faded. The headlines were full of doom and gloom. There were black

clouds overhead. The future seemed bleaker than ever. Not just for the economy, but for planet Earth itself.

Just three years earlier, American astronauts had sent back the first pictures of Earth from space. These stunning images

captured the fragile beauty of our common home, a precious crucible of life and the dead vastness of space.

And around the world, these pictures came to symbolise an idea that would challenge the complacent assumptions of industrial society.

Across the Western world, a new breed of intellectuals was advancing radical visions of a very different future. The coming

economic apocalypse they argued, was the least of our worries because what was at stake was nothing less than the future of

the planet itself.

The City, greedy for growth, spreading upwards and outwards, but every day less of nature. Every day, more of Man. This

is the shadow of progress.

Through heavy industry and our heedless pursuit of consumer comforts, we were destroying the fragile ecology of Spaceship Earth.

Doomwatch

The plight of our own green and pleasant land told the story. For the last quarter of a century, great swathes of

the British countryside had been smothered by concrete and tarmac. This was the heavy price we paid for progress.

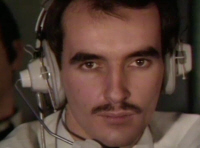

Nothing captured the anxieties of the emerging ecological movement better than the BBC series Doomwatch. Every week, a

crack team of scientists battled man-made threats to the natural world. From nuclear Armageddon to a plastic eating

virus that could munch its way through an aircraft.

Doomwatch attracted 12 million viewers, and even provoked calls for a Doomwatch parliamentary committee to investigate

environmental affairs.

Green Party

With Britain's major parties still committed to economic growth, perhaps it was time for a new political organisation.

And it was here, in industrial Coventry that Britain's first Green party was born.

Founded by disgruntled Tory activists, and of all things, an estate agent, the People Party first came to prominence

in the early 1973. And this is a copy of its first advert which was put in the classified section of the Coventry Evening

Telegraph. "Are you sincerely concerned about pollution, conservation, population, survival, ecology, and environment generally?"

It says. People want positive action now, in response to the doom watchers forecasts.

The people party were nothing if not radical, they were asking us to use less energy, spend less money, even have

fewer children. If they knew their policies weren't exactly crowd-pleasers, as one of them put it, it's a bit like

asking people of Coventry to vote for a permanent recession.

The Good Life

With such a doom laden message, it was perhaps not surprising that the people party didn't win much electoral support. But

outside the political arena, our home-made revolution was under way.

The Good Life charted the progress of Tom and Barbara Good, a middle-class couple who leave the rat race for a life of

self-sufficiency, with their neighbours watching in horror from over the garden fence. Tom and Barbara's hand-knitted

enthusiasm didn't arrive fresh from the writers imagination. It was based on the lifestyle choices of thousands of people

up and down the country, who'd been inspired to embrace a life of self-sufficiency.

So, you might have planted your vegetable patch, but what about the messier aspects of the self-sufficient life? John

Seymour's book the Complete Self-Sufficiency, was one of the more unlikely bestsellers of the 1970s. Probably not all

readers religiously followed its advice, on how to drain your land or slaughter your pigs. But it's true appeal lay

elsewhere, at a time of enormous economic disarray, with food prices heading through the roof, this book was your

insurance policy. And if things got really tough, it was your handbook for survival.

Today, self-sufficiency sounds terribly woolly and well-meaning. But amid the turmoil of the 1970s, its advocates

saw it as hard-headed preparation for an apocalyptic future, in which millions would have to flee the cities and fend

for themselves. And yet the most enduring environmental message of the era was altogether more cuddly.

Wandering across Wimbledon Common, making good use of the things that they found, the Wombles were pioneers

of recycling. 40 years on, we're all Wombles now.