Miners' Strike 1972

The Power of Militancy

The dream of a better life had even begun to penetrate some of the nations most traditional communities. All around the country

were our coal mining pits, where 300,000 men toiled deep underground, dangerous and often almost primitive conditions. Most of

Britain's miners worked six-hour shifts with just a 20-minute break to eat their sandwiches. At the Snowdon pit in Kent, eight

out of ten miners worked completely naked, because it was so hot underground.

During a shift, they lost so much fluid in sweat, that they had to drink 8 pints of water laced with salt. Little wonder, then,

that so many people saw them as a working-class heroes.

After the war, mining had become a nationalised industry, in recognition of the importance of coal to the country and of the

sheer courage of the men.

Miners' Club

But since then, the miners had been neglected, their wages falling far behind those of other manual workers. What made this so

infuriatingly for Britain's miners was that they felt that they were missing out on all the excitement of the affluent society.

They might have been the salt of the earth, but they, too, wanted their own homes, a foreign holiday, central heating and a

colour television. They didn't want to smash the system, they just wanted their fair share of Ted Heath's Brave New World.

Arthur Scargill

The miners' ambitions were pure '70s materialism but their industry had been built in the collectivist '40s and the truth

was, that a gulf was opening up between what ordinary families wanted and what our old-fashioned heavy-industry-dominated economy

could deliver.

In the pit villages of South Yorkshire, one young man became the standard bearer for the miners in patients for change.

Arthur Scargill "I don't believe that anybody in the trade-union movement wins anything at all, unless they're prepared to be militant."

NUM Headquarters

This is the headquarters of the Yorkshire NUM, for years the power base of one Arthur Scargill. We always think of

Scargill as the incarnation of hard-left militancy, and the sworn opponent of Thatcherite materialism. But the truth is

that his socialist rhetoric can be a bit misleading. What made Scargill is so successful was that he told the miners

what they wanted to hear. He loved his cheeky, flamboyant persona, but what they liked most of all was his promise to

get them more money.

Arthur Scargill "I've never known the employer who gives you anything. You'll get as much as you are prepared to go out and take."

"You get as much as you are prepared to go out and take." That's a young Arthur Scargill, expressing an almost Thatcherite ethos

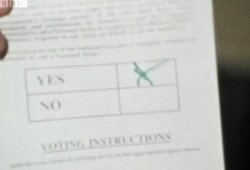

in 1970. The miners hadn't been out since the General strike of 1926. But in early 1972, they woke from their slumber and voted

to strike for a better deal.

Inside the government, there was no great alarm at the prospect of a national coal strike. The winter had been bailed and

coal stocks were high. But Ted Heath had fatally underestimated the miners. They had a new strategy up their sleeve. Across

the country, cast, mini-buses and coaches were sent out, carrying flying pickets to docks, coke depots and power stations.

In the early 70s there were a few laws restricting mass picketing. And it was soon apparent that the miners' mobile

tactics where choking the supply of coal to Britain's power stations.

The dispute reached a melodramatic climax at Saltley, near Birmingham, when thousands of miners and fellow trade

unionists, marshalled by Arthur Scargill, overwhelmed the police lines and forced the closure of the gates of the

Midlands' biggest coke depot.

Saltley Pickets

Saltley is a hugely symbolic event in our recent history – often seen as the moment when the miners forced the government

to its knees. But the truth is that Saltley was just a sideshow, because most of the coke had already been shipped out.

What really preoccupied the Cabinet that morning wasn't Saltley, it was the freezing weather, the blockade of the power

stations and the looming shortages. With barely two weeks power left before Britain sank into total darkness, Ted Heath

knew that the game was up.

Within the corridors of power, there was now a mood of abject panic. As Heath is right-hand man Willie Whitelaw put

it, "We looked absolutely into the abyss."

By now, power cuts were becoming a fact of life. Not only where power stations closing, but so were factories, offices

and schools. On the high Street shops were running out of matches and candles, on the roads, there were long queues as the

traffic lights failed.

What the politicians feared most was the loss of control. Heath's grand plan of a united, managed and modernised Britain

was unravelling economic collapse and social disorder. On Friday, 18th of February, the Cabinet met by candlelight and agreed

that they had no choice but to surrender. Two hours later, Heath welcomed the miners' leaders to number 10. As the night wore

on, the miners extracted not just the 27% pay increase they wanted, but a whole raft of extra concessions.

The strike was over. Heath hadn't just been beaten, he'd been annihilated!