Northern Ireland Troubles

The apparently, retaliatory bombings in Birmingham

Since the beginning of the decade, republican paramilitaries, Loyalist vigilantes, and the British Army had been fighting a

bloody battle to control the streets of northern Ireland.

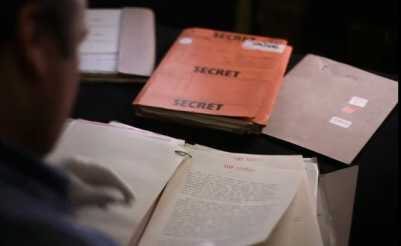

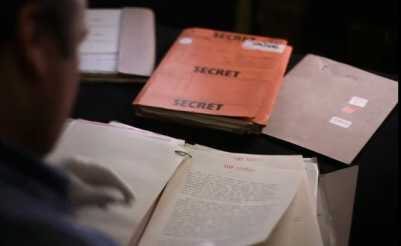

Harold Wilson was determined to come up with a solution. And buried in these recently declassified government documents is the

story of his attempts to find one. What all these top-secret documents show is just how far the Wilson government was prepared to

go to find a solution to the problems of northern Ireland.

Government Documents

So, for instance, they talked about redrawing the border, about giving Catholic areas to the Republic. They talked about

negotiating openly with the paramilitaries, and indeed they had already secretly started talking to the IRA.

David O'Connell

They discussed getting the United Nations involved to run the province themselves. And above all, Wilson contemplated what he

called the doomsday scenario, in which Britain would just unilaterally get out, and Northern Ireland would be left to sink or swim.

To many British observers, the conflict in Northern Ireland seemed an unfathomable relic of ancient history. But after years

of bloodshed, with no end in sight, the Republican IRA decided to copy the Marxist terror groups wreaking havoc in

continental Europe.

It was time, they thought, to take their struggle across the water, from the killing grounds of Belfast to the quiet

streets of middle England.

Military Vehicle

On 17 November 1974, the provisional IRA spokesman, David O'Connell, gave an interview to British television.

David O'Connell "Let me make this point, for five years the British government has had his forces waging a campaign of terror,

not just on the IRA, but on the people of Ireland. What have we got from the British public? From the British people? Total

indifference, they can wash their hands. We said last week in a statement that the British government and the British people must

realise that because of the terror they're waging in Ireland, they will suffer the consequences."

Four days later, in two Birmingham pubs, those consequences became devastatingly clear. It was payday, and in the city

centre, the Tavern in the Town and the Mulberry Bush were packed with young drinkers. That dreadful night, 21 people were

killed and nearly 200 injured by the bombs of the IRA.

The victims weren't policemen or soldiers, they were ordinary young men and women on an ordinary night out. In the immediate

aftermath, the public reaction was horror and fury.

After the horror of Birmingham, public opinion rallied against the bombers of the IRA. Wilson's doomsday scenario disappeared

into the filing cabinet, and the war went on. But Birmingham was also a terrifying reminder that nowhere in Britain was safe from

the violence that had engulfed Northern Ireland.

As one commentator put it, it was as though the vanguard of anarchy was loose in the world. Britain had entered a new age

of insecurity, when even going for a quiet pint could get you killed. That terrible day in November 1974 had raised the

spectre of the international terrorist, and 40 years on, we still live in the bomber's shadow.

As the clocks tick down to 1975, the harsh truth was sinking in that the British people were no longer masters of their

own destiny. Our island fortress had been overwhelmed by the tempestuous realities of a changing world. And nothing in our

economy, in politics, or our culture would be the same again.